To the Esteemed Ministry of Energy and Water!

Stories from Kabul No. 3 — The memo on my desk read “I. The Legal Environment in Afghanistan Generally.” It had been placed squarely in the center, with the notation Please read this first on a bright green sticky note. There were also a plethora of new office supplies and a box of business cards with “Jessica Wright, International Lawyer” printed on the front. I paused a moment to take in my new office – a corner, surprisingly – decorated with ornate Nuristani furniture and large photographs from the previous associate’s exploits in Bamyan, Mazar-e Sharif, and Samarkand. The floor to ceiling drapery, reminiscent of the Soviet Era, reminded me of the offices I’d visited in Delhi many years ago, and of the old train cars I rode from Warsaw to Krakow. There were piles of file folders and three-ring binders bursting with contracts and tax forms, and a gigantic fan threatening to blow them all away. Sunlight poured in through the large open windows, and with it, the dust that coats everything in a translucent film. I squinted to take in the view: an assortment of shrubbery, tall concrete walls topped with barbed wire, the backs of ostentatious houses three and four stories high, and in the distance, the mountains surrounding Kabul. I stepped onto the porch and heard children playing in the alleyways nearby, and the sound of clanking pots and pans from inside the houses across the way. “It’s safer to be in a slightly more residential neighborhood,” my boss later explained.

I suppose it should come as no surprise that “parties doing business in Afghanistan accept an inherent risk in relying on the unpredictable application of rules and laws by organs of the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan.” The memo continued, “The legal environment in Afghanistan is developing, and technical capacity at any level within the Afghan legal system cannot be relied upon. Processes and procedures are not comprehensively codified, and are subject to change without notice.” All of this was proven true a few hours later in my first meeting with the Ministry of Finance. In the absence of any real discrepancies in the firm’s accounting – we were in the midst of our yearly audit – the representatives were quick to invent new procedures, usually involving the procurement of various stamps, seals, and signatures, and inane retroactive requirements. Their primary goal, of course, was to elicit a bribe. Most companies in Kabul pay and get on with their business, but our firm has a zero tolerance policy for corruption. As one of the founding partners says, “The day we pay a bribe is the day we leave Kabul. If we’re just going to play into the system, we have no business being here.” This is something the Ministry auditors should have known. “We’ll see what we can do,” was their response as the meeting ended. Translation: we will now go back to the Minister and report that your filings are in order and that we can’t get any money from you, legally or illegally. Stand by for an assortment of hoops to jump through.

As to the Afghan body of case law and statutes, “laws often consist of no more than vague policy statements . . . legislative drafting in Afghanistan appears to be strongly influenced by the Persian poetic tradition, and therefore eloquence in the expression of legislative intent and elegant variation are often favored above technical precision and consistency … since the principle of stare decisis does not apply in the Afghan system, judicial interpretation cannot be relied upon to clarify interpretive voids …” That is a very daunting passage to read on your first day of work. The memo continued in a similar fashion, and on the last page my boss had scribbled, Welcome to the Afghan frontier.

It is now the twenty ninth day of the month of Sonbola here in Kabul, and the year is 1394. Work is busy and fascinating, and I’ve become more accustomed to the solar year and the Thursday/Friday weekend. I first realized we weren’t using the Gregorian calendar after preparing two lengthy tax briefs, both of which were returned to me with notes like, “Please see appropriate exchange rates for the months Sarantan, Hamal, and Sonbola,” and “You’ll notice that in Tax Year 1393, client reported x, y, and z, but the new tax law no longer requires us to account for those things in 1394.” The solar calendar, which I was only vaguely aware of until last week, begins on March 21st of the Gregorian year and ends on March 20th of the next. If you add 621 days to the solar year, you’re back in sync with the rest of the world.

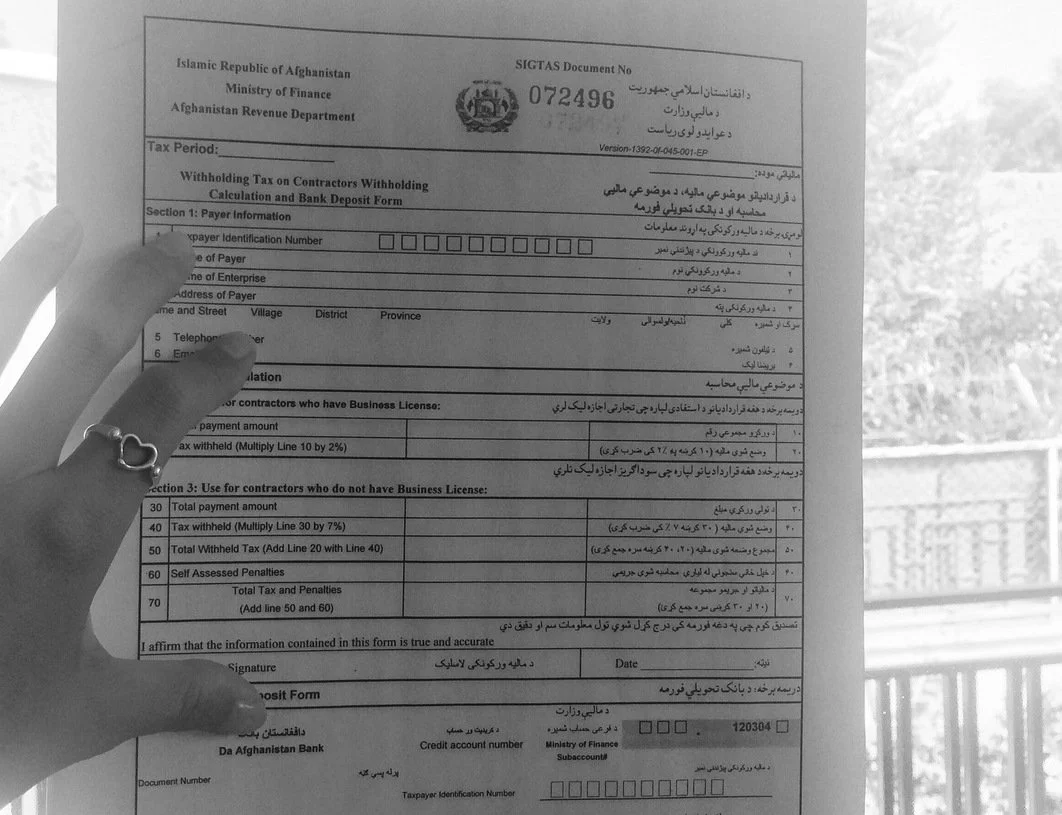

Most days it certainly feels like Kabul is running centuries behind. Our office deals with government agencies on a daily basis, and even simple legal tasks like filing tax forms can turn into month-long endeavors. Just last week, I was reminded to carefully separate and realign the carbon paper forms supplied by the Ministry of Finance for tax withholding because the bottom sheets weren’t legible. I spent a good part of the afternoon holding up sheet after sheet to the window to make sure all of the boxes and lines matched up. Once stapled together and filled out, the incongruent stacks had to be translated into Dari and then Pashto, stamped, signed, and hand-delivered once again to the Ministry.

The yearly tax audit is an ordeal of epic proportions that every company doing business in Afghanistan must endure. It usually involves several meetings with the Ministry of Finance in which everyone yells unrealistic requests and angry retorts at each other in their native tongue. During a meeting a few days ago, one of the auditors was shocked that our client, a large international company, had spent billions of dollars on employee salaries. He simply couldn’t wrap his head around the idea that a worldwide services company would spend that much on people’s paychecks. In the end, and without a trace of logic or reasoning that we could follow, he concluded that only half of that amount was legitimately spent on employee salary and the rest must have been paid to mercenary contractors who were to be taxed at a higher rate, of course. The meeting ended with a company representative yelling, “This is not how an audit works! This is arbitrary! We will not stand for this!”

Then there was the day I wrote a very frank and straightforward memo for a foreign client, a company that is owed a considerable sum of money by an Afghan organization. Years had passed and negotiations had yielded nothing, so our client wanted to bring a criminal claim before the Attorney General’s Office in Kabul. Unfortunately, the AG is the strong arm of the State in Afghanistan, and the best legal advice we could give was to do nothing. I wrote, in part, “The Attorney General’s Office targets all individuals for criminal investigation, innocent or not, who are in some way related to the case.” My boss frowned as he read it. “Do you want me to rewrite it in the passive voice?” I asked. He chuckled and said, “We’re beyond style here. Just make sure that if this falls into the hands of the government, we won’t become the new target.” I ended up writing, “While the Attorney General’s Office is a tool commonly used by local parties to apply pressure to other parties, it is not clear that (client) could rely on the appropriate application of the law in the event of a claim. The AGO has a tendency to investigate everyone involved in a case file, which is likely to include (client) personnel.” I'm not sure the fundamental message came through.

Registration of branches of foreign companies is also an ordeal. As a colleague summarized it, “First you need an introduction letter from the parent company. That has to be notarized. Then you have to get that notarized letter super notarized. After that you have to go to the state where the company is headquartered and get the state to verify that it has in fact been super notarized. Then you have to send it to the State Department and get, yes, you guessed it, John Kerry’s signature on the super notarized state verified letter, at which point they’ll send it to Afghanistan and you’ll have to pay the courier hundreds of dollars for the delivery. Once it’s here we have to run around to various ministries to collect stamps and an assortment of seals and signatures.”

We have Afghan clients, too, mostly small to medium-sized companies that are still waiting on payment for work performed under military or government contracts. Having met several of these businessmen (never women) and talking with them about their claims, I'm starting to get a better sense of the business culture in Afghanistan, which, as you can imagine, is very different from business culture in the west. For example, one client entered into a contract with a foreign government to build a police station in a distant province. He began the job by recruiting reliable workers and then sent them on the long journey to the work site with a considerable amount of supplies and machinery. As he explained, the only road to the remote location was dangerous given its rough condition, and significant parts of it passed through Taliban territory. The workers were risking their lives by traveling to the job site. Once there, communication was limited given the lack of telecom service in the area. When our client received a stop order from the government to halt work and spending, he had no option but to continue. Bringing the workers and supplies and machinery back to Kabul was unrealistic. It would have cost him considerably in money, time, and human life.

Fraud was also an element of the case above, as it often is in contractor/subcontractor cases. But “fraud” as a concept is surprisingly difficult to pin down in Afghanistan. In the west, if you fabricate receipts or pay a subcontractor less than agreed in order to line your own pockets, a court will most likely find that you acted fraudulently. In Afghanistan, a society that functions on cash and oral relationships between individuals and tribes, a fabricated receipt may be the best response to a demand by a foreign company to produce detailed accounting for every aspect of the project. Paying a subcontractor less for a job and pocketing the rest of the money may be a prudent business move if the company knows other, better subcontractors are blacklisted and that they will likely have to pay two or three lesser companies to finish the work. Unfortunately, there seems to be little cross-cultural understanding between western companies and governments and Afghan businesses. I am far from being an ethical relativist, but justice in these situations, I try to remind those involved, is situation-specific and hardly black and white.

Practicing law in Afghanistan is frustrating and difficult, and in my first two weeks I’ve found that a little humor goes a long way. I laugh at the little things, like the strange punctuation in memos addressed to government offices: "To Esteemed Ministry of Energy and Water!" and "To Respected Office of Bidding of Goods and Spare Parts!" Also, why is there an Office of Bidding of Goods and Spare Parts? Last week, I laughed about having to accompany one of our senior Afghan attorneys to the AGO where my sole duty was to “look imposing and express concern whenever the Attorney General raises his voice.” I wore my tallest heels and fanciest headscarf.

The highs are higher and the lows are lower in Kabul, and for that reason, there is a strong sense of camaraderie among the young lawyers and professionals living here. I certainly enjoy the perks of expat life – the embassy parties and brunches, yoga at the UN and circuits at ISAF, cooks and cleaners and R&R in Dubai. But ask almost anyone here what they do and why they do it, and you will get a thoughtful and heartfelt reply that never includes the phrase, “for the money.” The paths to Kabul are many and varied, but everyone who lives and works here day in and day out wants to see a prosperous Afghanistan. And for those of us who believe in the rule of law, we don’t mind the uphill battle.