Warlords & Takeout

Stories from Kabul No. 2 — Mostly, I was exhausted. There was the packing and repacking, a sleepless night of anxious thoughts, the flight from Milan to Istanbul, and a four and a half hour layover in the dead of the night. When I arrived at the overcrowded international terminal at IST, a dark sense of dread came over me. I ordered a venti chai tea latte, bought two bags of Haribo Gold Bears, and sat in front of the lounge monitor watching Go To Gate flash across the screen for destinations like Najaf, Sulaimaniyah, and Baghdad. When “impoverished, Taliban-infiltrated, suicide-bombed city” is all you have to associate with your destination, it’s hard to rally. Kabul – 3:10 – Wait for Gate. I wasn’t overcome by the urge to buy a one-way ticket back to Chicago, but as the minutes ticked by slowly I became increasingly angry with myself for having made this decision in the first place.

I couldn’t quite will myself out of the lounge on time, so I ended up sprinting down the terminal to the gate where all but one anxious-looking man had been loaded onto the bus. He was inquiring about his checked luggage. “Sir, you have two checked bags loaded on the plane sir,” said the gate check staff. “No, I only checked one bag,” he responded. With a chuckle, “Well sir, now you have two!” He and I were the last two passengers on the bus that would take us to the outer reaches of Atatürk International. I remember passing rows of shipping containers and other miscellaneous cargo and wondering if I hadn’t read the fine print well enough.

The flight was full of Westerners. Men with buzz cuts, prominent biceps, and army green t-shirts, tall bespectacled Dutch men with reporter notebooks, women wearing Western tunics and headscarves and speaking the language of project management. A beautiful Afghan girl with kind and vibrant eyes sat next to me. She looked very stylish in her elegant black tunic and hijab, and we struck up a conversation about Islamic dress. She asked me if this would be my first time in Afghanistan – pronounced in a lilting and graceful accent – and then enthusiastically told me all the things she loves about her country. Later, I fell asleep to her conversation with another Afghan woman, the singsong words bale, bale playing in my head. Dari, the Afghan version of Persian and one of the national languages of the country, is really beautiful.

I woke in time to see the sun rising ahead of us in the east, and as we approached Kabul, the desert disappeared and the Hindu Kush came into view. I thought about Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Little Prince and his tiny asteroid, and about the surface of Mars and the moon. “Kabul might as well be outer space,” I whispered to myself. Without an airline ticket, one could be stuck forever in this place surrounded by a vast mountain range encased in endless deserts. The city itself appeared brown and dusty and flat, and from above, the rows of concrete buildings gave the impression that we were landing in the middle of a sprawling detention center or military compound. But as we began the descent I felt a rush of adrenaline and excitement. I had finally made it to Kabul and there was no room for panic.

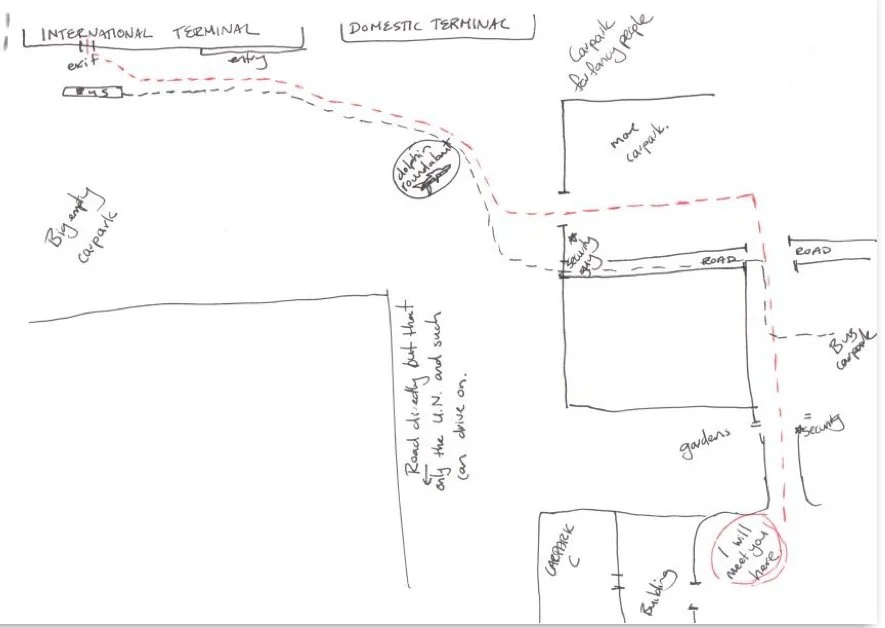

The hot, dry air smelled like summer in Mumbai, but the atmosphere at Hamid Karzai International was more subdued. An Afghan man loaded my suitcases onto a cart, and we exited the building and began the dreaded walk from the international arrivals terminal to the entrance and parking lots. I felt exposed in the open air, but more curious than frightened, and I managed to snap a few pictures of the “gardens” – wilting rosebushes among weeds – as we made our way to the gate. Given the recent airport bombings, I thought I would be sick with fear, but the ten-minute walk felt strangely normal. A coworker greeted me warmly at our meeting point, and we set out to the city with our driver.

The next hours are a blur of checkpoints, men with guns, and perilous moments on a journey through Kabul’s manic “streets.” When we finally arrived at the guesthouse, I met my housemates – journalists, NGO researchers, communications specialists – as well as the very gracious guards, drivers, and cleaners who make life here easier. We have gates and high walls, 24-hour guards, CCTV, a safe room, and a semi-automatic weapon. Even so, we live “outside the wire,” to borrow a military phrase, which means our security approach is to remain under the radar and as out of sight as possible. Our cars have no markers, we wear headscarves and abayas, and we do not keep regular schedules.

Though more and more organizations are opting for compounds and armored vehicles, I’m not sure it’s worth coming to Kabul to live within concrete walls, your every move dictated by inflexible and often irrational security restrictions. In my first five days, I've moved around the city with relative ease, pausing anxiously only once or twice when passing a checkpoint or sitting too long in traffic. I don’t wake up in the morning seized by fear, and for the most part, the days pass by in a normal rhythm. But I guess this is the reality in a conflict zone. Everything’s fine until it isn’t. You’re safe until you’re in the wrong place at the wrong time. You forget about the danger until your friends get captured or killed. It’s the vague, speculative fear, I suppose, that looms large.

My first week in Kabul has been filled with takeout dinners at home, homemade English breakfast, all day brunches in private gardens, and bonfires at night. These are things you wouldn’t think possible in Afghanistan. I’m excited about the work – more on that later – and happy to have met many interesting, slightly eccentric, enthusiastic people. The low-flying helicopters that regularly shake the house still throw me off, as do the glimpses of abject poverty seen through the car window. I like hearing the call to prayer five times a day, but the light blue burkas, the chadri, that completely cover the body with a single piece of thin cloth, are an eerie reminder of the Taliban’s hold on this country.

As we ventured into a different neighborhood a few nights ago, our driver pointed to a newly built, outsized mansion and said, “That is Dostum’s house.” I looked on in awe as I recalled Ahmed Rashid’s description of General Rashid Dostum, the Uzbek warlord:

“He wielded power ruthlessly. The first time I arrived at the fort to meet Dostum there were bloodstains and pieces of flesh in the muddy courtyard. I innocently asked the guards if a goat had been slaughtered. They told me that an hour earlier Dostum had punished a soldier for stealing. The man had been tied to the tracks of a Russian-made tank, which then drove around the courtyard crushing his body into mincemeat, as the garrison and Dostum watched. The Uzbeks, the roughest and toughest of all the Central Asian nationalities, are noted for their love of marauding and pillaging – a hangover from their origins as part of Genghis Khan’s hordes and Dostum was an apt leader. Over six feet tall with bulging biceps, Dostum is a bear of a man with a gruff laugh, which, some Uzbeks swear, has on occasion frightened people to death” (Taliban, pg. 56).

Somehow, all of us, even warlords and lawyers, have a role to play in this strange but fascinating place.

This essay was published as the first in a series of Dispatches from Kabul for the St. John’s Law Center for Law and Religion, and featured in the Spring 2016 St. John’s Law Alumni Magazine.